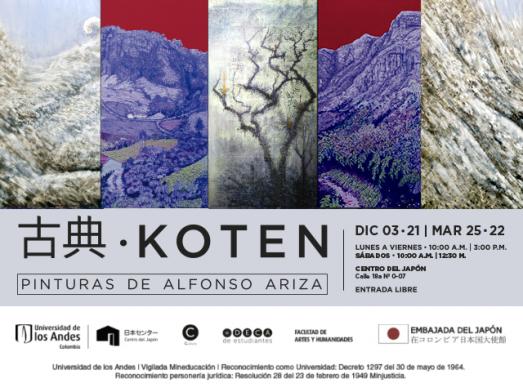

The Japanese government oversees a wellknown system by which to designate special monuments and artworks as “National Treasures” (Kokuhō). Less well nown is the fact that Japan also designates select practitioners of the traditional arts as “Living National Treasures” (Ningen kokuhō). In doing so, it ensures the vitality and transmission of a wide range of arts and crafts that are centuries old, but whose practitioners have dwindled in the modern era. The artists thus designated are understood to be living manifestations of cultural patrimony, who embody rare artistic legacies. Were this system extended overseas, then surely Alfonso Ariza would be an ideal candidate to receive such a designation. This is because through his painting Ariza manages to preserve, transmit, and nourish the practice of Nihonga, a tradition that is quintessentially Japanese, but at the same time transform it into something new and remarkable. The result is showcased in the three unique paintings of the exhibition “Koten.”

Nihonga is a mode of painting that is based upon traditional Japanese formats, materials, palette, and subject matter. It amalgamates the approaches of many different schools of painting from the premodern era and adapts them for the exhibition spaces and viewing conditions of modern times. Its genesis dates back to the 1880s, when art critics and intellectuals in Tokyo such as the American Ernest Fenollosa (1853- 1908) and Okakura Kakuzō (1862- 913) expressed grave concern over the westernization of Japan and the potential demise of its time honored traditions. These two figures were instrumental in the opening of the Tokyo Art School (Tōkyō Bijutsu Gakkō) in 1889, which represented the first western style art academy that did not teach oil painting, but instead offered instruction in Nihonga (an oil painting curriculum would be added in 1896). Meanwhile, in Kyoto, a parallel movement to preserve and modernize Japan’s traditional schools of painting was taking place among artists such as Takeuchi Seihō (1864-1942).

The Nihonga movement has been successful beyond the wildest imagination of its founders. Today there are a number of prominent art schools that offer a rigorous training curriculum in Nihonga, graduating scores of students. Dozens of exhibitions take place every year, attended by large audiences. Many of Japan’s greatest modern painters are Nihonga artists, and their works are not only found in museums and private collections, but also adorn traditional institutions such as Buddhist temples and the Imperial Palace. Alfonso Ariza received a Ministry of Education (Monbushō) Fellowship to study in Japan, and received his Master’s Degree from the Tama Art University (Tama Bijutsu Daigaku) in Tokyo. There Ariza studied among others with Kayama Matazō (1927-2004), one of the most renowned Nihonga masters of the postwar era.

Nihonga is exceedingly difficult to master. The many pictorial traditions it folds into itself are best explained in terms of traditions of monochrome and polychrome painting. Monochrome painting consists of water-based ink, and is predicated upon the artist’s ability to apply myriad types of brushwork and inkwork. Despite its seeming simplicity, an artist who has mastered ink painting can conjure an unimaginable range of colors, textures, moods, and atmospheric effects through their use of strokes, wash, layering, splashing, and staining. Polychrome painting traditionally consists of ground mineral pigments—such as azurite blue (gunjō), malachite green (rokushō), and shell white (gofun)— ound with animal glue (nikawa). Here, too, the artist’s ability to modulate the intensity and color of pigments by grinding them to different granule sizes, or combine them with underlayers of white pigment to soften them, can generate a broad range of artistic effects. Nihonga artists can also avail themselves of other materials, such as gold and silver leaf (kinpaku and ginpaku), which add a wondrous metallic aura to the canvas. The combination of ink painting, vegetable dyes, mineral pigments, and decorative foil ensures that Nihonga can offer an infinite of visual qualities across its surfaces.

Painting format is also an important component of Nihonga, in particular the six-panel screen. Such screens, known as byōbu, are a traditional component of Japanese visual culture. They evolved from earlier Chinese screens in such a way that they could be folded, xylophone-like, due to the paper hinges between each of the panels. Folding screens could be easily folded, transported, and stored, which was important because their display was usually temporary and occasion-specific; they were brought out for the brief duration of a ceremony or social occasion, and then put away. Whenever they were displayed, they formed space cells within an architectural interior, and their painted surfaces animated these spaces with meaning and atmosphere. And because Japan was a floor-sitting culture for most of its history, viewers were immersed in the visual fields of these large screens surrounding them. Whenever a byōbu was brought out, it transformed a space and transported viewers to another world.

Ariza has clearly mastered the materials, formats, and traditional approaches to Japanese painting through his study of Nihonga. But he has also gone much further by using these components in new ways and adapting them to a new environment. Not all of these materials are readily available outside of Japan, and any artist hoping to continue the traditions of Nihonga in the Andes will have to be resourceful and make adaptations. I was surprised and delighted, upon a visit to Ariza’s studio in 2019, to witness not only his works-in-progress, but also his remarkable library of mineral pigments, and some of the devices he was using to grind and make them, sometimes experimentally, much like the laboratory of a Renaissance painter.

The three paintings of the “Koten” exhibition showcase different aspects of the Nihonga tradition, but also various ways in which Ariza has introduced a new chapter to this tradition. The Heart of the Earth reveals a wondrous understanding of the power of the screen format. It depicts a waterfall in the Amazon Jungle, and its all-over rendering of the water achieves a sublime effect. The powerful rhythm of traditional Taiko drumming, to which Ariza says he was listening while creating the work, imbues every square inch of the painting. The pigments, which include quartz crystals, not only convey the foam and wave crests of the ocean, but add a unique texture to the surface – a mineral depicting a liquid. Could you imagine kneeling down before this screen, so that your sightline was in the middle of this roiling sea, as would have been the case in premodern Japan?

Silver Threads, Life Threads, meanwhile, is predicated upon the unique materiality and decorative effects of Nihonga. At its center is La Chorrera, a waterfall near Bogotá in the midst of a forest. It is painted upon a ground of silver-leaf foil (ginpaku), and the shimmering, refractive light of the silver leaf suffuses the landscape with a mystical quality, as if it is glowing with an inner light. Here the silver ground also bears semantic meaning. Ariza states that he uses it to manifest what for him constitutes the true treasure of the El Dorado Legend, which are the natural resources of the continent, and especially its water. The waterfall can be likened to silver threads that connect to rivers and extend throughout the land, constituting the circulatory system of the earth. The painting proposes that El Dorado was never a specific place, but instead was always all around us.

The Way of Liberation also draws inspiration from its locale, but in a different manner. Here the soaring landscape of the Andes is rendered against a red sky, symbolizing the blood shed during the War of Independence when Simon Bolivar crossed the mountains along this road. Here too, in keeping with Ariza’s unique approach to the Nihonga palette, the materiality of the red pigment is pregnant with meaning. It consists of cochineal red, traditionally drawn from insects in various parts of Latin America, and highly admired throughout Europe for its brilliant color. Attempts to reproduce it accidentally led, somehow, to the invention of the synthetic dye Prussian (Berlin) Blue, which was then exported to Japan. In the nineteenth century, Japanese artists such as Katsushika Hokusai took advantage of Prussian Blue to design new landscape prints with wondrous effects, such as The Great Wave. In using cochineal red in The Way of Liberation, therefore, Ariza brings the journey of this wondrous color full circle.

The title of the exhibition, “Koten,” can be translated as “Classic,” which I understand to be an homage to the traditions of Nihonga painting Ariza admires so much in Japan. Although Nihonga simply means “Japanese Painting,” one is tempted to refer to Ariza’s practice as Sekaiga, or “World Painting.” We often speak about cultural and artistic traditions as national ones, but he is a living example of the fact that no artistic tradition can be confined within the boundaries of one nation or culture. Through his work, Nihonga continues to evolve into new chapters, gain new inspirations, and find new audiences that the founders of the movement could never have imagined.